This is a write-up of the first 18 years of history of Pymunk. It's adapted from the talk 18 Years of Falling Objects: Lessons from Maintaining Physics Library Pymunk I presented at PyCon Sweden in October 2025.

If you are only interested in the Pymunk changelog, for example to see what was new in a release of Pymunk, you should instead go to the Pymunk Changelog. This post is probably not what you are looking for - But you are of course very welcome to stay!

Pymunk was created in 2007. I wanted to make a game with realistic 2D physics for the bi-annual game competition PyWeek, where you have to write a game from scratch using Python in a week. However, at that time no good 2D physics library for Python existed, and I did not want to write any advanced physics algorithms as part of the competition.

The rules of PyWeek allow for participants to use code written before the competition starts. But they have a smart rule: As long as the code is packaged up as a library that is available for everyone to use, and it is released at least 1 month before the competition starts, then it is allowed. (For the exact details, see The PyWeek Rules)

And this is what I did, the first version of Pymunk was hacked together of 5 parts:

This was then packaged as a zip-file and released as Pymunk 0.1 at 2007-08-01 20:35.

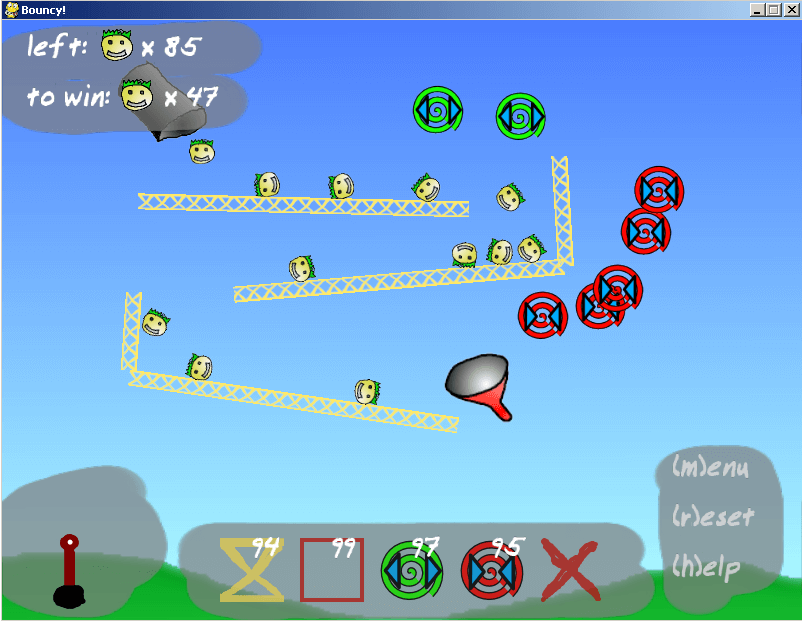

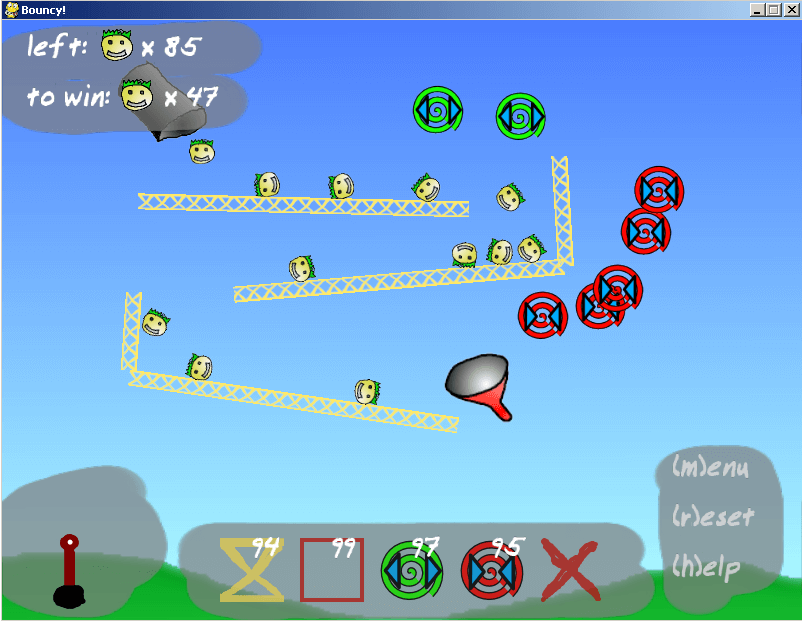

A friend, Srekel, and I, wrote the first game using Pymunk in a week, and submitted it as our entry into PyWeek 5. The game is called Bouncy, and is a 2D physics puzzle game.

The goal of the game is to get a number of bouncy "heads", that spawn from a metal pipe in the top left corner of the screen, to the funnel at the other end of each level. To your help you have objects with different properties. By placing these strategically the balls will be guided into the goal.

It wasn't our best game, and together with the cumbersome installation process of Pymunk at the time the game didn't do that well in the competition. But what it did do is that it proved that Pymunk worked and it was possible to use it to get nice 2D physics in your game!

After about a year Pymunk was more polished than its initial 0.1 release, and I posted a release announcement to the python-announce mailing list in June 2008.

Hi everyone,

Im glad to announce that pymunk 0.8 have been released, a

library wrapping the 2d physics engine Chipmunk.

You can find it here: http://code.google.com/p/pymunk/

What is pymunk?

===============

pymunk is a wrapper around the 2d rigid body physics library

Chipmunk, http://wiki.slembcke.net/main/published/Chipmunk It

puts a pythonic layer above chipmunk to make it easy to use

for python programmers. The main goal with pymunk is to make

2d physics easy to include in your game/project.

It is (or striving to be):

* Easy to use It should be easy to use, no complicated

stuff should be needed to add physics to your

game/program.

* "Pythonic" It should not be visible that a c-library

(chipmunk) is in the bottom, it should feel like a python

library (no strange naming, OO, no memory handling and

more)

* Simple to build & install You shouldnt need to have a

zillion of libraries installed to make it install, or do

a lot of command line trixs.

* Multiplatform Should work on both windows, nix and OSX.

* Non-intrusive It should not put restrictions on how you

structure your progam and not force you to use a special

game loop, it should be possible to use with other

libraries like pygame and pyglet.

Its licensed under MIT just as Chipmunk, so everyone should be

able to use it.

What is new?

============

This is the first release I actively promote, and the latest

additions made up to this release is a better build script,

automatic vector conversion and a number of small improvements

here and there.

/Victor - main pymunk developer

(vb at viblo.se)

At this time more things were in place, and much more polished compared to the very first versions. In addition, the Pymunk vision was already more or less complete. As seen in the announcement above it more or less matches today's vision in the Pymunk readme, just worded slightly differently.

To be able to learn the vision behind a library is something I appreciate, then I know what to expect.

Finally, in 2010, 3 years after the initial release, Pymunk 1.0 was released! The big new feature motivating a 1.0 release was Python 3 support, but it also contained smaller improvements of course!

In contrast to many other projects upgrading Pymunk to support Python 3 was not that complicated. I opted for simultaneously supporting both 2 and 3 at the same time, which turned out to be the right choice for Pymunk.

This is also the year when the first scientific papers using Pymunk were published. See Pymunk Showcase for a list of all papers (that I know of) using Pymunk, by now its quite a long list!

If Bouncy was the first game ever written with Pymunk, then SubTerrex was the first game that actually looked good. A very cool looking cave exploring game by Paul Paterson - I was very impressed when I first saw it!

You play as a cave explorer descending down into a procedurally generated cave. To help, you have flares for visibility and ropes, simulated with Pymunk.

I have never been interested in money for Pymunk. I have a day job and prefer to keep Pymunk as a hobby without any money involved. In 2013 someone asked for a donation link for the first (and only) time. At that time I did have a note in the README that asked users to send me a physical(!) postcard if they enjoyed Pymunk. Naturally, that is what I replied, either send me a physical postcard, or if the user really wanted to donate then donate to the underlying Chipmunk2D library which appreciate the donation more.

However, no one ever sent me any postcard (and I'm not sure if this user ever donated to Chipmunk2D).

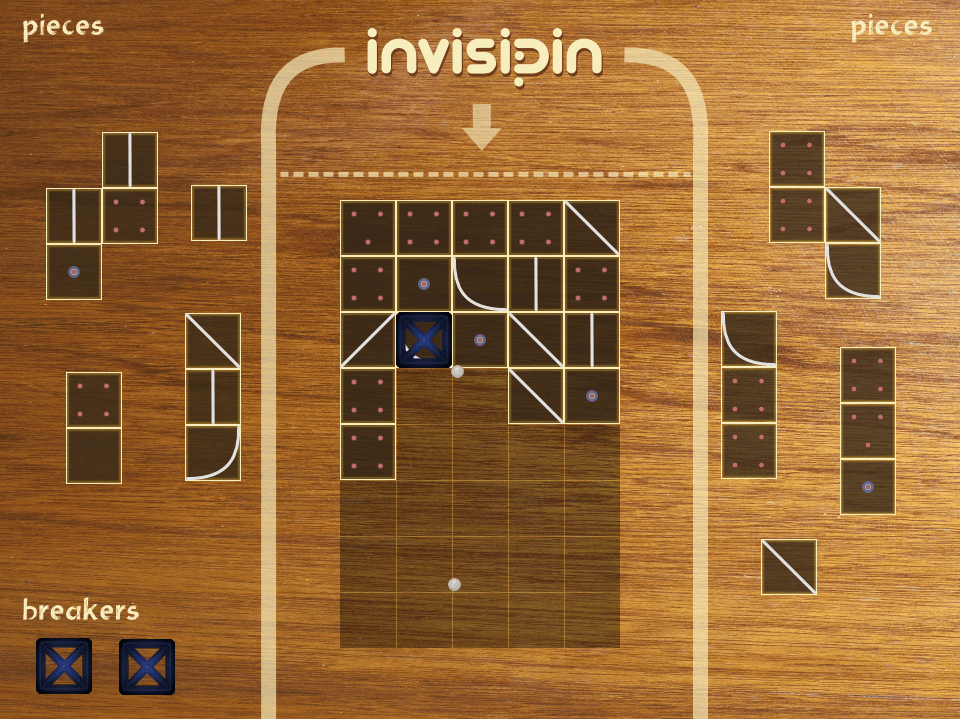

Pymunk was created to make it easy to use realistic 2D physics in the PyWeek game competition. In 2015, it finally happened, a game using Pymunk won PyWeek! Invisipin is a cool Pachinko-like puzzle game written by Tee for PyWeek 20.

This is arguably the biggest architectural change Pymunk has undergone. Up until this point Pymunk used ctypes to interface with Chipmunk2D (the c library that runs the actual collision detection and collision resolution algorithms). However, it had some downsides:

CFFI improved on all 3 of these.

Now, in 2025, the situation is a bit different with less hype and interest around PyPy, easier multiplatform compilation (cibuildwheel and easier build agents). It might be time to revisit the binding layer again.

The game Invisipin (the PyWeek winner from 2015) is not the only game using Pymunk that has received an award. In 2016 a team made Beneath the Ice for the team competition in PyWeek 22.

This is a really cool game where you play as a submarine under the ice. To help you, the submarine is equipped with a harpoon which lets you shoot enemies and interact with objects in the water.

By 2020 it felt like type hints had become stable and useful enough that Pymunk could and should implement them. Pymunk doesn't have that big API surface, and not any tricky-to-type APIs, so shouldn't be too difficult to add. Or so I thought!

It turns out that the type hints were not as mature as I thought... but on the upside it forced me to connect with the broader Python community while trying to fix it. Below is an example which the current version of Mypy could not type:

>>> body = pymunk.Body()

>>> body.velocity = 20, 0

>>> body.velocity

Vec2d(20, 0)

>>> body.velocity = 2 * body.velocity # Not allowed!

Naturally I went to Github and Mypy's issue tracker, where someone already had reported this missing feature in issue #3004 already in 2017. Guido van Rossum (the creator of Python!) had already replied by the time I found the issue, with this:

IIRC we debated a similar issues when descriptors were added and decided that

it's a perverse style that we just won't support. If you really have this you

can add #type: ignore.

Ord och inga visor

as we would say in Swedish! But, I was not (too)

discouraged from this, maybe something changed since that comment? I wrote

this followup question on the Issue:

Is there some workaround for this problem which does not require the consumer of the property to use#type: ignoreon each property usage? I have a library Im trying to add type hints to, similar to the (very simplified) code below, and this problem comes up a lot.class Vec: x: float = 0 y: float = 0 def __init__(self, x, y): self.x = x self.y = y class A: @property def position(self): return self._position @position.setter def position(self, v): if isinstance(v, Vec): self._position = v else: self._position = Vec(v[0], v[1]) a = A() a.position = (1, 2) print(a.position.x)

And now the magic happened. The same day(!) as I posted that question van Rossum replied!

Use ‘Any’.

His reply was short, but still very cool! I was a bit star-struck to have such a key Python figure answer my naive question 🤩.

It did however not really help, even after I got some additional support. There were no good workarounds for Pymunk's case. For quite some time users of Pymunk have had to live with this shortcoming. However, in 2025 Mypy finally added support for this case, and if you look at the issue today you will find it closed with a fix merged. It turns out that Pymunk's use case was reasonable after all!

One of the highlights in 2021 was when the below video showed up in my LinkedIn feed.

I'm not often browsing the feed in LinkedIn, but by chance did it this time. I didn't know it was Pymunk, but thought it was such a cool demo that I wanted to try something similar myself. And then when I investigated I found out he had used Pymunk under the hood! A very cool showcase of Pymunk I think!

Another cool thing that happened in 2021 was the publication of the paper Moral dynamics: Grounding moral judgment in intuitive physics and intuitive psychology. I think this is the most unexpected usage of Pymunk I've seen! I encourage you to go and check out the abstract. Apparently Pymunk can be of use even in psychology research!

Something that had been on my mind a long time were how to handle Pymunk's dependency on Chipmunk2D. It is a great library and has been indispensable for Pymunk. But, for the last 5 years it has been mostly dead, with no new releases and only a very very tiny amount of activity.

At the same time I had previously done some experiments which showed that even small changes to Chipmunk2D could yield a performance boost (5%), and more invasive / breaking changes could very likely do a lot more. Slembcke, the creator of Chipmunk2D clearly stated that he doesn't see a lot (or any) changes to Chipmunk2D coming, and considers its API/ABI stable, and even suggested a "turbo"-fork as one way to do new features.

So, in 2025 I decided to take the leap and made an official fork of Chipmunk2D called Munk2D. At the time of writing this post not much more than that has happened, it took quite a bit of effort to understand and update its documentation and surrounding infrastructure.

Finally, on Pymunk's 18th year I presented its history at PyCon Sweden 2025, in a talk named 18 Years of Falling Objects: Lessons from Maintaining Physics Library Pymunk. It was my first time attending a Python conference, and PyCon was well-organized and interesting to attend! But maybe even more fun was to prepare the talk, since I had to look back over Pymunk's history, not something I do every day.

Pymunk is as active and healthy today as it was 5, 10 and 15 years ago! I plan to continue in a similar way for the foreseeable future. Stable, steady improvements, which hopefully leads to many cool projects!

Finally, as I think shows from this history write-up, what I like the most of Pymunk is all its users. Big thank you to everyone using Pymunk and let's hope for at least another 18 years of progress!